Culture Within Whale and Dolphin Societies

Until recently, culture was one of the stand-alone characteristics that defined the human species. However, the better we study and understand our fellow animal species, the clearer it becomes that we are not that special after all. The notion that animals may have cultural traditions is not that new after all. Even Aristotle noted that hand-reared songbirds that were exposed to songs of other species, made different sounds than their parents. Therefore, he suggested that chicks learn to sing from their parents.

It is not even the first time that we have to grand capabilities to other (non-human) animals that were believed to be unique to humans: Once tool use was considered a unique feature of humans. This belief was crushed thoroughly – from great apes and elephants to sea otters, some birds, fishes, and octopi: they all use tools. New Caledonian crows even create their own tools. Now, tool use is only one of many aspects of the cultural life of many non-human animals.

To further complicate the discussion around culture, there is no one definition of culture that all scientists agree on. This lack of a concise definition has fueled the decade-long discussion around the topic of non-human culture. Generally, it’s agreed that non-human culture includes the adoption and transmission of particular behaviors in a group. Questions in the ongoing debate are, for example, about how human culture and non-human culture differ from each other and whether they are equivalent. On the one hand, some scientists argue that human culture is uniquely human because it arises from language and symbolism and creates moral norms. On the other hand, the study of culture as a biological and evolutionary phenomenon is now well accepted. So, get ready for some amazing behaviors researchers have been able to document in whale and dolphin species all over the world.

The “sponging” dolphins of Australia

Let’s start with a “marine” example from a warmer place than Iceland before looking at cetaceans in our own waters. A population of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins living in Shark Bay, Australia, was among the first in which researchers detected signs of cultural traditions. First documented in 1984, some of these dolphins pluck sea sponges off the seafloor and fit them over their beaks. With this “sponging” technique, they are protecting their beaks from rocks and sharp corals when looking for bottom-dwelling fish. However, not all dolphins exhibit this behavior. It is mostly female bottlenose dolphins, and they will teach their offspring how to do it. Especially female calves are likely to become “spongers” if their mothers were known to use this foraging strategy. This behavior allows them to exploit a food source that is inaccessible to non-sponging dolphins. A comparative genetic analysis of the sponging and non-sponging dolphins of this population ruled out genetics as a driver for the sponging behavior – instead, cultural transmission is most likely responsible for the spread of this technique. As of now, scientists have documented at least three generations of sponge-wielding dolphins.

A female Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin in Shark Bay uses a sponge to protect her face while hunting on the seafloor. (Credit: Dolphin Innovation Project)

Another behavior in the same dolphin population that has been documented more recently is the so-called “shelling” or “conching”. It is a foraging behavior, too, in which dolphins use an empty shell to catch and eat. Conching takes some skill and practice, and only a minority of dolphins in this population have mastered it. Rather than learning this behavior from their mothers (vertical transmission), the dolphins are learning this behavior from their peers (horizontal transmission).

An Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin in Shark Bay, Australia, catching a fish in a gastropod shell. This foraging behavior is called “shelling” or “conching” (Credit: Sonja Wild/Dolphin Innovation Project)

Killer whales: It is not all black and white

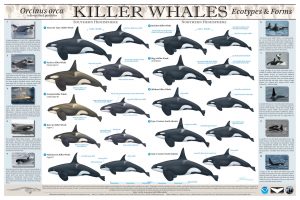

Another example is killer whales, also called Orcas. Currently, scientists distinguish between at least 10 different ecotypes among the global killer whale population. That means that even though as of now all Orcas worldwide are still considered a single species, they are far from all being or behaving the same. What is particularly remarkable, is that even populations of killer whales that live in the same area do have different cultural traditions and dialects. Scientists can distinguish different ecotypes just by listening to their vocalizations. And killer whales are fussy eaters, too: They only feed on the type of food, that their mothers and other family members have taught them to.

Also, Orcas of different ecotypes will not breed with one another. They will only mate with Orcas belonging to their own ecotype. Since there has been no gene flow for 150,000–700,000 years, different ecotypes differ genetically from each other and also in their morphology, i.e. the way they look. Below you see shows a male and female of each of the 10 ecotypes that have been recognized so far. They reach different sizes as adults and both the saddle patches behind the dorsal fin and especially the shape of the white eye patches varies between ecotypes. Scientists advocate the recognition of at least some ecotypes as subspecies or even species in the future – soon there might be officially more than one species of Orca out there!

Here in the North Atlantic, two different ecotypes are recognized, called Type 1 and Type 2 (very imaginative). Below can see that Type 1 remains smaller than Type 2 with an average size of 6.6 and 8.5 m, respectively. The Orcas seen in Iceland waters are often Type 1. They are highly skilled hunters of Atlantic herring and have developed special hunting strategies to catch it. Other fish prey includes mackerel and salmon. Also, many orcas in Norway belong to

Type 1 and feed on Herring in the fjord systems. However, some type 1 killer whales also feed on seals and harbor porpoises. Type 2 killer whales, on the other hand, are mostly feeding on other marine mammals.

What young humpback whales learn from the adults

The humpback whale is one of the main species we see on our tours off the coast of Reykjavík. So, let’s have a look at them, too. At first sight, humpback whales do not seem as social as bottlenose dolphins or orcas. However, they, too, have feeding techniques that individuals learn from their peers, e.g. lobtail feeding. This is a slight variation of a better-known feeding technique called bubble-netting. It was hypothesized that this behavior was initiated as whales in Alaska switched from feeding on herring to sand lance. Since then, researchers were able to show that it has spread through cultural transmission. Like Australia’s bottlenose dolphins, humpback whales are learning from their peers.

This photograph taken with a small drone in Antarctica shows several humpback whales creating a bubble net to herd krill together. Credit: National Marine Fisheries Service https://www.sealifer3.org/news/humpback-bubble-nets

Another example is the famous song of the humpback. It is an extraordinary example of vocal cultural behavior. Researchers have even detected patterns of song evolution and revolution among the populations (14). Humpbacks seem to have a tendency to learn novel songs. In the southern hemisphere, interactions between humpbacks from different breeding populations are possible on their circumpolar Antarctic feeding grounds. These interactions generate revolutions in song patterns moving from one population to the next. This means, whole populations rapidly and collectively substitute their song for a new version. In the northern hemisphere, however, populations from the North Atlantic and North Pacific are separated by continents which prevents cultural influence between populations of the two oceans. This explains the more gradual change of the songs in Northern populations in which song revolutions have rarely been documented. Here, the populations need to generate new song material themselves and cannot copy other populations.

What should you take home from all this?

There is no question that more research is needed to figure out how much cultural transmission in animals resembles that in humans. We are probably still only scratching the surface, but can see that cetaceans have developed complex and impressive culture.

Culture also has important implications for conservation. Without us being aware, a population might be subdivided into cultural groups, like the different ecotypes of Orcas. If conversation efforts focus on only one group, it might lead to a loss of diversity. It has also been shown how human disturbance can cause cultural changes in non-human animals.

For culture to play a bigger role in conservation, we need to create a public awareness of non-human animals having a culture in the first place. As mentioned in the introduction, to many anthropologists it probably does not make a lot of sense to call anything that non-humans do culture. If one focuses on language and symbols, that seems very reasonable. For evolutionary biologists, on the other hand, culture is an alternative information stream besides genes. From this perspective, the differences are more of degree than kind.

Accepting the presence of culture in other species than our own would go against our anthropocentric view of the world and we would perhaps finally have to say goodbye to our throne as the crown of creation. But would that be so bad?

If you made it all the way to the end, I assume you might be interested in learning a lot more about this topic. In that case, I highly recommend the book “The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins” by Hal Whitehead (Dalhousie University) and Luke Rendell (University of St Andrews).

Blog by Hanna Michel, Special Tours Guide