Why Do Whales Migrate?

Migration is the regular, repeated movement of an individual or group of individuals between two or more locations. Migration usually occurs over relatively long time scales – periods of weeks or months rather than hours or days.

Among cetaceans, migration is most well known in baleen whales. Most species migrate between polar and temperate feeding areas in summer and subtropical to tropical breeding and calving areas in winter. These are large-scale, seasonal movements, that most (if not all) of a population undertakes.

Gray whales are champion migrators, travelling up to 25,000km on their annual round trip from Mexico to Siberia. Image from the International Whaling Commission.

But why bother? These long journeys are very energetically costly, especially for pregnant females or mothers with young calves. In addition to this, while temperate and polar regions – baleen whale feeding grounds – are rich in prey, the tropics are relatively sparse and finding prey there can be difficult. At first glance, migration doesn’t appear to have much benefit to whales.

There are four main theories that explain why baleen whales make these arduous journeys every year.

Cold water

One theory is that whales move away from their feeding grounds before calves are born because these cold waters would pose a risk to the young calves. However, smaller marine mammals than baleen whale calves can endure these seas year-round, so the low temperature may not present much of a risk to the relatively large calf. Perhaps a more pertinent concern would be the rough and dangerous sea conditions in temperate and polar regions over winter.

Following food

Although these colder regions are much richer in marine life – and therefore prey – during summer, they are ruled by the seasons. In winter, food becomes more scarce. After taking full advantage of the summer boom near the poles, the warmer, tropical seas have enough to provide for baleen whales during their ‘fasting’ season.

Escaping killers

Killer whales, despite being cetaceans themselves, are the most significant threat to baleen whale calves. Although this apex predator is found throughout the world, killer whales are less abundant in the tropics than in temperate regions. Therefore, migrating to these relatively safe, warm waters before giving birth to their calves means that baleen whales can keep their young out of the reach of predators when they are at their most vulnerable stage.

Ancestral heritage

The fourth and final suggested driver of migration is that it is part of their heritage and culture – baleen whales migrate like this because their ancestors did. In the past, when colder waters were nearer to the equator than they currently are, these migrations would not have been as long. Therefore, the energetic benefit would have been much greater: a season of intensive feeding in very rich, cold water increases the whales’ energy reserves which in turn increases their chances of successful reproduction. Over time, as cold water retreated poleward and ice masses melted, these migrations became gradually longer and longer.

Although general consensus now is that killer whale predation is probably the most important driver of migratory behaviour, any or all of these factors could be involved.

Most of the baleen whales that we see around Iceland are migratory, visiting to feast on the rich array of plankton and fish in the waters here over summer. But not all baleen whales make the trip back south – some stay over winter without returning to the breeding grounds. This is evidence that baleen whales do not have to migrate.

Indeed, some do not migrate at all. Notably, the bowhead whale remains in freezing Arctic waters for the whole year; although they move seasonally between different regions, this species does not undertake long journeys between distinct feeding and breeding grounds, nor do they undergo migratory fasts. At the other extreme, Bryde’s whales live in tropical regions for the whole year and do not migrate to colder feeding grounds. And, despite generally being a migratory species, the population of fin whales in the Mediterranean do not migrate either.

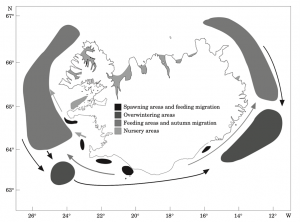

Although the term ‘migration’ is most associated with the great whales and their immense annual journeys, this is just one way in which cetaceans migrate. For example, killer whales in Iceland move between different regions at different times of year. This migration is not associated with distinct breeding and feeding grounds: the killer whales migrate because their prey do. Icelandic herring move between their overwintering grounds and their summer spawning grounds, and the killer whales follow them.

Icelandic herring shoals migrate between their overwintering grounds and their summer spawning sites. Image from Jakobsson and Stefánsson, 1999.

Not all Icelandic killer whales are herring specialists, and not all of them have seasonal movements that are closely tied to the herring. For example, some killer whales which feed on herring in Iceland during the winter travel to the north of Scotland in summer to hunt seals there.

Whether they are herring specialists or have a taste for seal, Icelandic killer whales follow their prey. These movements are regular, repeated, and cover long distances and time scales – in other words, a migration!

So there are many reasons why whales and dolphins migrate, and many different ways in which they do so. From the record-breaking pilgrimage that gray whales make up and down the Pacific coast of America, to the sea ice-dictated movements of beluga whales between open sea and coastal estuaries, to the killer whales which follow their prey on their own migration. Cetaceans, it seems, are ruled by the seasons just like us. And here in Iceland we should be especially grateful for this, as it is the changing of the seasons that brings these wonderful creatures back to our shores, year after year.

Written by Eilidh