The mystery of the puffin in winter

Written by Daniel Blankenheim.

Winter is here! And because of fewer daylight hours and the cold, we have reduced the number of our whale watching departures each day. With the boats being less busy, I find myself helping out in the reception a lot more. I‘m surprised about how many times I have heard the following question in the last couple of weeks: „We would like to see puffins. Can we join one of your tours to see them?“ I get it; puffins are extremely appealing and cute birds. People travel from all over the world to see them here in Iceland, where we have the biggest breeding population of Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) on the globe. But the short answer to the question is: „No, unfortunately you cannot!“ It‘s not my devilish nature that I don‘t want our guests to see the puffins, but they are simply not around anymore. They migrate away after the summer. The more interesting question is: where do these millions of puffins go so suddenly at the end of the summer? What is their life in winter like? Well, let me tell you all about it. We are here to unravel the mystery of the puffin in winter.

Atlantic puffin at sea in the beginning of winter.

What we often explain on our tours during the summer in a jokingly manner is that the puffins get tired of the colony life and need some time off. In fact, they are mostly solitary during the winter, whereas they are very gregarious and have an active social life during the breeding season in summer. Once they are gone, they spend the winter months out on the open sea, somewhere in the vastness of the North-Atlantic ocean, possibly without touching soil for up to eight months. That‘s definitely one of the many „Wow!“- moments on the tours.

It is interesting to note, though, that the exact winter migration of the puffins is poorly understood and little studied. While it is very easy to study puffins during the summer months in their colonies, studying individualistic behaviour during the winter is very difficult. Some new research, especially with the rise of tiny geolocators has shed light on what used to be completely uncertain. Brace yourself for a few more „Wow!“ moments!

Not all puffins migrate to the same places. They show great variability in where they travel during the winter and how they get there. Some birds migrate over 1,700 km away and others stay within 250 km of their colony to which they always return for the breeding season (the same one, like frogs) (5). The record seems to be one individual who was found to have covered 7,700 km (4,800 mi) of the ocean in eight months, traveling northwards to the northern Labrador Sea then southeastward to the Mid-Atlantic before returning to land (7). At the same time, and somewhat surprisingly individuals show remarkable consistency in their own migratory routes among years.

It seems like they trust their own „gut feeling“ more than the word of their neighbours. Beside the fact that routes are very different among individuals (which implies that there is no genetic fixation of migration routes), you also have to keep in mind that most pufflings (baby puffins) will fledge in the middle of the night, leaving the nest and their parents behind. That means that migration routes are also not taught by the parents. It seems more likely that each indiviual learns and explores their own winter route and that they will stick to it for better or worse. How they always find back their own routes and navigate in the often featureless open sea, we simply don‘t know (1). Crazy isn‘t it?

A puffin in flight

But why is it important at all to understand where the puffins go in winter? It is crucial to know more about these puffins because the time out at sea accounts for two-thirds of the year or up to eight months (3). This period is crucial for the puffins to prepare for the breeding season. In a study focusing on puffins that breed in Scotland and Norway it was shown that their body mass increased by 20–30% between the chick-rearing period and the end of winter (2). So, if conditions are favourable, the fitness of the puffins is increased, which means that they rear their offspring more successfully. This is, in the long run, essential to save the declining population across the globe.

In general female (but not male) winter foraging efforts seem to be very important for reproductive success. Their pre-breeding condition, is critical for successfully having offspring. And although this seems to be of greatest importance, get ready for a Hollywood romance story: there is an interesting study (8) in which they found that pairs that followed more similar routes bred earlier and had a higher breeding success the following spring. Moreover pairs can benefit from following similar migration routes by synchronising their returns and reunion, which in turn increases reproduction success. Isn‘t that beautiful?

While some puffins remain social throughout the year, most puffins live a very solitary life out at sea with a population density as low as 1 bird per km2 (6) and even split up from their partners. They really seem to need their space! Of course that‘s the secret to a healthy relationship and these romantic and very monogamous puffins truly understand that. Independence yes, but always think about the team in the long run!

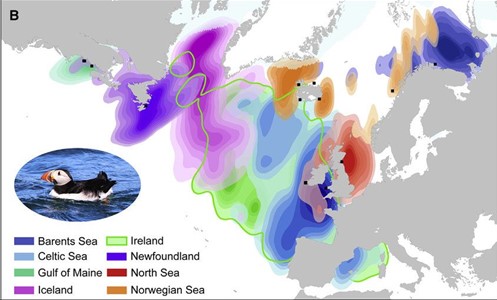

Atlantic puffin distribution (taken from Fayet et al., 2017)

Different puffin populations have different migration behaviours. And they mostly overwinter in different areas, allthough there are certain areas where populations overlap. These areas are especially crucial for protection. If we find their crucial feeding sites and wintering locations, we can stop oil exploration, commercial fishing and even offshore wind parks in these areas by protecting them (5).

There are many factors influencing how far puffins will migrate away from their summer breeding colony. One of the more important ones seems to be the size of the colony: the bigger the colony, the more the puffins have to compete for a given food source (5). So if you have a big colony, like in Iceland with up to 10 million individuals during the summer (4), resources near the colony might be depleted more quickly which might lead birds to exploit more distant areas and spread more.

On the other hand, a recent study from Maine (closer to the southern end of the Atlantic puffin distribution) found no evidence of inter- or intra-colony differences in overwinter movement. Puffins mostly stuck close to each other and remained relatively close to the breeding site (9). It seems like food is abundant enough here to sustain the smaller Maine population.

What we now see is how complex the winter migration is and how difficult the question about where they go to really is. Some will stay in the cold but abundant waters of the North, while others might go for a winter „holiday“ in the Mediterrenean sea. Some stay closer to their partners, some don‘t. Many of the mechanisms influencing these decisions remain unclear. We need more research to really understand the mystery of the winter puffin.

For you, dear reader, it means that you will have to come back to Iceland. Enjoy the beautiful and magical Goddess Aurora dancing in the night sky above iceland in winter (and maybe even enjoy New Year’s Eve here!) and come back to see the adorable puffins when they breed here in summer. You could also buy a boat including crew that takes you out into the North-Atlantic ocean to try to see the puffins in winter. Good luck and as always thanks for reading 😊.

Sources:

- Guilford T, Freeman R, Boyle D, Dean B, Kirk H, et al. (2011) A Dispersive Migration in the Atlantic Puffin and Its Implications for Migratory Navigation. PLOS ONE 6(7): e21336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021336

- Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Jens-Kjeld Jensen & Michael P. Harris (2018) Fit is fat: winter body mass of Atlantic Puffins Fratercula arctica, Bird Study, 65:4, 451-457, DOI: 10.1080/00063657.2018.1524452

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/scientists-have-cracked-the-mystery-of-where-puffins-winter

- https://www.nordicvisitor.com/blog/5-things-may-not-know-puffin/

- Fayet AL, Freeman R, Anker-Nilssen T, Diamond A, Erikstad KE, Fifield D, Fitzsimmons MG, Hansen ES, Harris MP, Jessopp M, Kouwenberg AL, Kress S, Mowat S, Perrins CM, Petersen A, Petersen IK, Reiertsen TK, Robertson GJ, Shannon P, Sigurðsson IA, Shoji A, Wanless S, Guilford T. Ocean-wide Drivers of Migration Strategies and Their Influence on Population Breeding Performance in a Declining Seabird. Curr Biol. 2017 Dec 18;27(24):3871-3878.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.009. Epub 2017 Nov 30. PMID: 29199078.

- Boag, David; Alexander, Mike (1995). The Puffin. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2596-6.

- “Cabot discovery”. Audubon: Project Puffin. National Audubon Society. 2013. Retrieved 19.11.2022.

- Fayet AL, Shoji A, Freeman R, Perrins CM, Guilford T (2017) Within-pair similarity in migration route and female winter foraging effort predict pair breeding performance in a monogamous seabird. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 569:243-252. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12083

- Mark A. Baran, Stephen W. Kress, Paula Shannon, Donald E. Lyons, Heather L. Major, and Antony W. Diamond “Overwinter Movement of Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica) Breeding in the Gulf of Maine: Inter- and Intra-Colony Effects,” Waterbirds 45(1), 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1675/063.045.0103

- Image of Atlantic puffin at sea in the beginning of winter: https://coastal-connection.co.uk/blog/2020/9/16/winter-puffin. Retrieved 19.11.22.